To identify and map evaluations of interventions on gang violence using innovative systematic review methods to inform future research needs.

A previous iteration of this map (Hodgkinson et al., (2009). “Reducing gang-related crime: A systematic review of ‘comprehensive’ interventions.”) was updated in 2021/22 with inclusion of evaluations since the original searches in 2006. Innovative automatic searching and screening was used concurrently with a ‘conventional’ strategy that utilised 58 databases and other online resources. Data were presented in an online interactive evidence gap map.

Two hundred and forty-eight evaluations were described, including 114 controlled studies, characterised as comprehensive interventions, encompassing more than one distinct type of intervention.

This suggests a substantial body of previously unidentified robust evidence on interventions that could be synthesised to inform policy and practice decision-making. Further research is needed to investigate the extent to which using automated methodologies can improve the efficiency and quality of systematic reviews.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gang membership and associated violence is recognised as a social problem associated with negative and often devastating outcomes for individuals, families and communities. In addition to criminality, gang membership is associated with drug use, poor education and employment outcomes, mental health problems, social deprivation and inequality, all of which are both determinants and consequences of gang violence (Bellis et al., 2012, Coid et al., 2013). Historically, the social problem of gangs was seen to be concentrated in US cities; today however the existence of youth gangs is recognised internationally (Hazen & Rodgers, 2014; Higginson & Benier, 2015). Across continents, most victims and perpetrators of violence are males.

Gang members commit many more serious and violent offences than non-gang members leading to arrest, incarceration and often a lifelong impact on a person’s psychological and social functioning (Thornberry et al., 2003). The evidence shows that gang membership increases knife crime and gun use and accounts for 50% of knife crime with injury and 60% of shootings (Bullock & Tilley, 2017). In the UK, there has been a 36% rise in recorded knife crime since 2012 (HM Government, 2018) with nearly 41,000 offences with a knife or sharp object reported to the police in 2021 (Grahame & Harding, 2018). The impact of violence on the UK NHS was estimated to be £2.9 billion in 2012 and on society in total £29.9 billion per year (Bellis et al., 2012).

Broadly interventions that target gang crime can be categorised into those that adopt a criminal justice response focused on social control and those that go beyond the criminal justice system to include social improvement. Criminal justice interventions use sanctions to stop gang crime including legal provisions such as gang injunctions and curfews whilst social improvement interventions are varied, commonly including direct messaging to gang members or those at risk, recreation and diversionary activities, community mobilisation, mentoring and advocacy, provision of increased economic opportunities, educational programmes, vocational training, psychological therapies and collaboration between agencies (Hodgkinson et al., 2009).

Intervention programmes can be categorised into primary, secondary or tertiary types of prevention. Primary prevention interventions are aimed at all young people to prevent them from joining gangs (Esbensen, 2000). For example, the Gang Resistance Education and Training programme provides a school-based curriculum delivered by law enforcement officers to resist delinquency. Secondary prevention targets youths with risk factors for joining gangs (Esbensen, 2000). For example, the positive youth development approach uses mentor-supported wilderness expeditions to build developmental assets such as positive values and coping and social skills (Norton & Watt, 2014). Tertiary prevention interventions target youth who have already become involved in gangs (Esbensen, 2000). For example, focussed deterrence strategies that utilise a combination of law enforcement, community mobilisation and social services (Braga et al., 2019).

Three reviews focusing on specific prevention interventions (Fisher et al., 2008a, b) or interventions in developing countries (Higginson et al., 2016) found no evidence. A WHO overview (World Health Organisation, 2015) identified that the only systematic reviews to find evidence of any positive effects on gang violence were comprehensive interventions. This included a review by Hodgkinson et al., (2009) which this current work is building on. In their review, comprising a map of 141 studies, and an in-depth synthesis of 17 comprehensive interventions, meta-analytic results of 9 studies showed a positive but statistically nonsignificant association with crime outcomes.

The use of automated ways to identify and classify studies at scale has become an active area of methods research and methodological development, with the potential to improve coverage and reduce waste in research costs worldwide (Marshall et al., ). Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG) was one of these approaches pioneered in a collaboration between the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre (EPPI Centre), Microsoft™ and Cochrane, with more than 50 machine classifiers built and integrated in EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al., 2020). MAG was an open-access dataset comprising > 250 million bibliographic records of published research articles from across science, connected in a large network graph of conceptual, citation and other relationships. The OpenAlex dataset has since incorporated and superseded MAG Footnote 1 and is being continuously updated. In this review, we employed both conventional Boolean database searches alongside automated MAG and OpenAlex searches.

Evidence maps are one of a range of new evidence synthesis methodologies developed to meet the different objectives evidence synthesis can support (Miake-Lye et al., 2016). In contrast to a systematic review, a systematic map aims to describe the key characteristics of the evidence base but does not produce a meta-synthesis of findings to evaluate the effectiveness or process of interventions (Schmucker et al., 2013, Gough et al., 2017). This approach is beneficial to informing future research efforts by identifying research gaps, informing future research needs and avoiding duplication of effort if the current evidence base is sufficient to inform policy and practice (Sutcliffe et al., 2017, Saran & White, 2018).

This paper reports on a systematic map conducted in 2021/22 and is part of a larger body of work commissioned by the NIHR to synthesise the evidence of interventions for gang crime (Hodgkinson et al., 2009). It will expand the scope of the previous review to include prevention and a broader range of outcomes beyond criminal justice measures.

The following research questions (RQs) are addressed:

After consultation with advisory groups, the review protocol was finalised, and the review registered in PROSPERO (Hodgkinson et al., 2020). This review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (Moher et al., 2009), adapted where necessary, to accommodate the evidence map approach taken.

To be included in the map, papers needed to meet the following criteria:

Our search strategy included three strands:

Titles and abstracts returned by all search strategies were exported into EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al., 2020).

Two information specialists (CS and AC) designed and implemented the search strategy with input from the wider review team.

The search was developed around the two concepts of (1) gangs, including terms for named gangs and for population groups vulnerable to gang membership, and (2) generic and named interventions for preventing, desisting or reducing gang violence, including study designs implying interventions. English was applied as limiter in some databases. The search was developed in PsycInfo using controlled vocabulary, keywords, title and abstract fields (see Appendix 1). This was adapted to each source and simplified where needed. See Appendix 2 for details of the 33 databases searched, between July and September 2021 and the 25 websites and search engines that were searched and browsed between 13 and 16th September 2021.

Two different kinds of automated searches were conducted.

The first was a ‘network graph search’ run on 25th May 2021. MAG was used to conduct a semantic network analysis to identify records related to a set of ‘SEED’ studies that comprised 90 of 141 ‘included’ records in the original map (Hodgkinson et al., 2009). This search automatically retrieved the set of MAG records that were (on the search date) connected within the network graph to the ‘seed’ MAG records. Studies were connected either via a ‘one-step’ forwards (‘cited by’) or backwards (‘bibliography’) citation relationship, and/or via a ‘one-step’ forwards (‘recommended by’) or backwards (‘recommends’) ‘related publications’ relationship (using the ‘bi-directional citations and recommendations’ network graph search mode in MAG Browser).

The second was a ‘custom search’, run on 16th September 2021, which was conceptually similar to a ‘conventional’ electronic search strategy (see previous section) comprising keywords and indexing terms, combined using Boolean operators; and it operates in the same way, retrieving records that contain specified keywords in title or abstract fields, and/or those ‘tagged’ with specified indexing terms. The custom search is reproduced in Appendix 3.

All records retrieved by the MAG searches were semi-automatically de-duplicated using ‘manage duplicates’ features, and the retained records were assigned for potential screening.

Forward and backward citation searching using OpenAlex (within EPPI-Reviewer) was undertaken for the 67 papers—at the time of the search, July 2022—included in the in-depth stage of the review (currently in progress); relevant references identified through these searches were also included in the map.

The reference list of studies included in the most relevant reviews that focused specifically on gang crime was also manually assessed for relevant articles.

Title-abstract screening was conducted using ‘priority screening mode’ in EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al., 2020). All title-abstract records retained for potential screening were initially prioritised by a machine learning algorithm designed to prioritise and rank the records based on a score that represents the likelihood of a record being considered eligible for inclusion in the current study. This machine learning algorithm was initially trained using 12,695 title-abstract records that had previously been screened for the original map and/or in-depth review, of which 141 had been ‘included’ in the 2009 review (Hodgkinson et al., 2009). In ‘priority screening’ mode, the list of records yet to be screened is continually reprioritised based on the algorithm which evolves as the ‘machine’ progressively ‘learns’ from the accumulating corpus of eligibility decisions (‘included’ or ‘excluded’), with the aim of placing those unscreened records most likely to be eligible at the top of the prioritised list, to be manually screened next.

Screening (successively by titles, abstracts, full text) and data extraction were conducted predominately by MR after a pilot stage and interrater agreement of 90% with JH.

Progress was monitored using the ‘screening progress’ record in EPPI-Reviewer, to inform when the number of includes had plateaued indicating that we had screened most of the relevant studies in the prioritised list. The title and abstract screening was stopped after 14,315 studies and 2845 were identified for full-text screening. These 2845 records were subsequently re-screened using narrowed design criteria (see above). The records not screened at title and abstract were categorised ‘as-yet-unscreened by humans’. These records have been set aside, but also retained in the pool of unscreened records that will be replenished and then reprioritised for potential screening after updating our searches in any future update.

We extracted pre-defined descriptive characteristics listed below. As the studies may have been conducted in more than one country, and can include more than one type of prevention intervention, population and outcome, these codes are not mutually exclusive.

Where full-text papers were not retrievable abstracts were coded where sufficient detail was reported. For linked records (i.e. 2 or more records looking at the same study), one was marked as the “base” study and the related record(s) were added to this record so that they could be considered collectively. To prevent double counting, the records of the linked studies were then marked as excludes so they are not part of the active records in the review.

The data were described narratively but not synthesised (Pettricrew & Roberts, ).

In order to provide a publicly accessible overview of the studies, an online interactive evidence gap map was produced, using v.2.2.3 of the EPPI-Mapper software (EPPI-Centre, 2022). Data was extracted from EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al., 2020) and input into the app, where display and filter choices were chosen.

The advisory group, with representatives from Public Health England (PHE); West Midlands Police (WMP), College of Policing (CoP) and the West Midlands-based Gangs and Violence Commission, a local community-led organisation commented on the protocol and will comment on the findings at in-depth review stage.

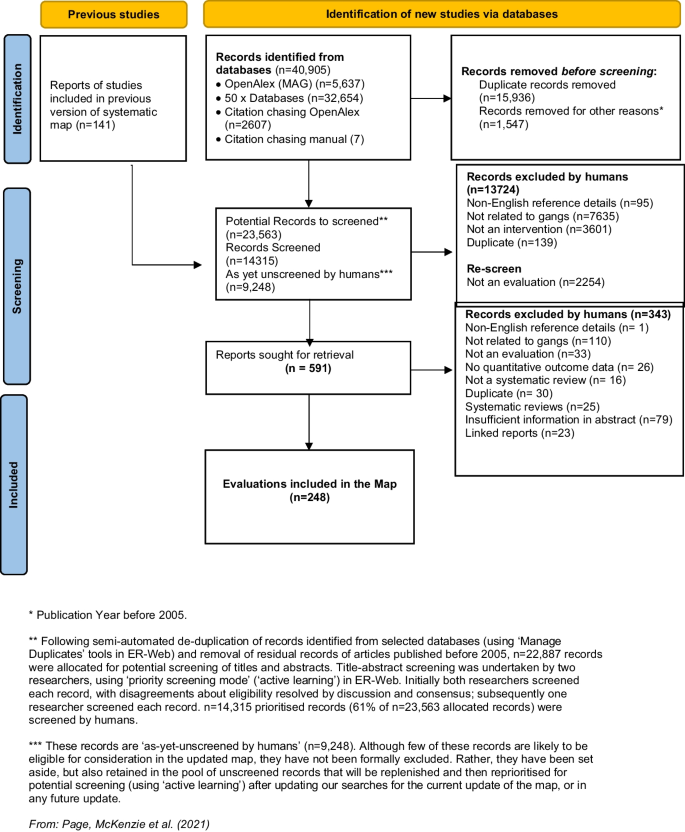

The conventional, automated and citation chasing searches located 40,905 potential citations for inclusion in the review. Duplicates were removed and studies from the previous review (Hodgkinson et al., 2020) were added resulting in 23,563 potential citations to screen. A total of 591 citations were identified as potentially relevant from title-abstract screening. Three hundred and forty-three records were excluded from the map as they either did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 241), were not obtained in full text (n = 79) or were linked records that were combined with a selected “base” study and therefore not active records in the review (n = 23). Two hundred and forty-eight evaluations were mapped. A list of excluded items (with reasons) is available on request. The flow of literature through the review is shown in Fig. 1.

Tables 1 and 2 detail the characteristics of the included papers.

Table 1 Characteristics of when and where included papers were conducted Table 2 Characteristics of population, intervention, control group, outcomes and other markersTable 1 shows that since the millennium, there has been a steady increase in the availability of studies, reflecting an expanding field of interest and evidence in this area: pre 2000 (n =18 studies); 2000–2004 (n = 16 studies); 2005–2009 (n = 47 studies); 2010–2014 (n = 70 studies); 2015–2019 (n = 77 studies); 2020–present (n = 20 studies). Overall, this suggests a substantial body of new evidence to synthesise. Table 1 shows that most of the papers identified, reported on evaluations conducted in North America (n = 208), some in the UK (n = 21) and South America (n = 6) with very few from anywhere else in the world. The country was unclear in three studies.

Table 2 shows that over half of the interventions (n = 155) were tertiary (for gang members); just over a third were secondary for at risk groups (n = 89) and 36 were primary targeting all young people.

Many interventions included either both criminal justice and social improvement strategies (n = 106) or social improvement strategies only (n = 107); some were categorised as criminal justice only (n = 35). Thirty were coded as ‘other’ to capture studies where the focus was on violence or policing more generally (and unclear whether at risk or indicated specifically for gang membership) and where the studies were surveys of intervention providers.

Among the two criminal justice intervention categories, enforcement was coded more frequently (n = 126) than legal interventions (n = 35).

A range of social improvement intervention elements were coded; these are listed in terms of frequency from most (n = 141 for education) to least (n = 17 for situational/physical changes to the local area) in Table 2.

Eight were coded as ‘other’ as they did not fit into the typology (including police reform, conditional cash transfers, mock emergency department resuscitation; school policies and programmes, service provider surveys and interventions with poor descriptions). Twenty-eight included ‘other’ in addition to codes from the typology to capture content mentioned above, plus evaluations of local authorities, incentives, social media based interventions, studies with a myriad of interventions not easily codable and when family, schools and other settings such as open facilities were central to intervention.

In terms of study design, n = 153 were controlled studies whereas n = 95 did not have a comparison group.

Among the outcomes, criminal justice measures were most frequently reported (n = 158), followed by associated behaviours and cognitions (n = 110). The remaining measures were assessed relatively infrequently including public health measures (n = 34), education (n = 29), socio-economic (n = 15) and cost (n = 12). Eighty studies included other types of outcomes; these were mainly process measures, assessment of potential displacement effects, personality assessments and measures of family or peer relations.

Other population markers are reported in Table 2 in order of frequency with geographic area being identified most frequently (n = 132), reflecting the territorial nature of gangs and other educational institutions (such as special schools) the least (n = 1). Table 2 indicates that interventions that target gang crime sometimes include families, schools and participants on probation or in prison. The ‘Communities’ and ‘Agencies’ codes denote when the study participants included members of the community or agency members in a survey evaluating effects of intervention.

Of the 248 evaluations mapped, the majority of interventions (n = 180) were identified as comprehensive, involving a combination of criminal justice and social improvement approaches or at least two social improvement components specified in Table 2. The cross referencing of comprehensive intervention (n = 180) with controlled design (n = 153) led to the identification of 114 studies. This is a substantial increase compared with the original review that included 17 studies in the in-depth review only 9 of which had a control group. The volume of studies that are both comprehensive and controlled is encouraging both in terms of the relevance and robustness of evidence available for in-depth synthesis.

The interactive online map, available at https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/35/Maps/gmam/, cross references intervention components with selected population and study characteristics of the studies and allows users to see where the evidence is and where gaps exist. A ‘filter’ tab enables users to focus on a particular set of information; it is possible to filter by (1) outcomes, (2) other population markers, (3) type of prevention or (4) publication date. The bibliographic details of each study and a link to a publicly accessible full text version of the paper (where available) can be accessed by clicking on an individual cell within the map. For more information on how to use the online map, please refer to the ‘About this map’ section of the map.

Conducting a systematic map of reviews has provided a robust method to explore the breadth of available intervention evaluations in the field of gang violence. Innovative automated machine learning methods were utilised alongside more conventional methods to showcase these evolving methodologies. The online map created for this project provides a visually accessible snapshot of the landscape of evidence that focus on gang violence and can also be used interactively to filter by interest. Results show that there has been an increase in the volume of research published investigating the impact of interventions to reduce gang violence and a substantially higher volume of robust studies with control groups and interventions identified as comprehensive (n = 114). Whilst a range of outcomes were used in evaluations, criminal justice measures and associated cognitions and behaviours predominated. Relatively few studies included public health, education and/or socio-economic outcomes and only a minority of studies included some sort of cost analysis.

Despite the increase in evaluations of interventions for gang crime, whilst there is some coverage across continents it is apparent that most evidence is generated in a North American context. Given the worldwide phenomena of gang-related violence, the results suggest that that practitioners and commissioners should be supported to robustly evaluate the effectiveness of preventive gang programmes in other parts of the world (Higginson et al., 2016).

Given the volume of interventions located, there may be sufficient evidence to explore research questions about the direction and size of effects of comprehensive interventions. Further, the range of available interventions suggest that it may be possible to explore questions about the characteristics of effective interventions and the mechanisms they operate through, i.e. what works, for whom, in what respects, to what extent, in what contexts and how?.

Despite the prevalence of comprehensive interventions, few interventions or evaluations explicitly framed gang-related violence as a public health issue and relatively few included health, education and socio-economic outcomes. Where these outcomes were included, these were measured at the individual level, rather than at a structural level. Omission of these measures prevents exploration of the impact of interventions on important risk factors for gang crime and therefore we encourage the assessment of such measures in future evaluations of gang crime. Similarly, cost analysis of the interventions which is necessary to evaluate the interventions’ efficiency in addition to its effectiveness would be beneficial.

Whilst gang-related research is mostly evaluated in North America, these results may reflect bias as only studies in English were included. As is common in reviews, we were not able to locate 13% (79) of the articles identified and screened as potentially relevant (a list of these is available from the lead author). The difficulty of accessing papers highlights the need for developing improved methods for retrieving papers in systematic reviews. Additionally, although hand-searching of relevant websites was conducted, we cannot be certain if and to what extent publication bias has impacted on the map findings.

We followed the rigorous standard procedure developed at the EPPI Centre in the production of this map. However, the coding of studies was based on the information available in the report. Retrospective decoding of intervention content is especially challenging often due to poor descriptions of the interventions, for example in journals, and therefore coding decisions necessarily involved some inference. This indicates that the development and use of shared, reliable typologies of intervention content would not only support replication and implementation of research findings but also the accumulation of evidence across studies. We acknowledge that the Hodgkinson et al. (2009) typology is a first step in this process but requires further work.

This review models the use of innovate search technology in combination with conventional search methods. However, more research is needed to investigate the extent to which using the OpenAlex dataset as a single source can improve the efficiency of study identification and coverage for systematic reviews. Better understanding of any trade-offs between the relative advantages of using automation—potential cost and resource savings—and any impacts on evidence quality needs to be evaluated.

The criteria in the original map were broader including protocols and overviews; thus, not all of the papers in the original map were included.

This review was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). PHR Reference Number: NIHR129814 ‘Comprehensive’ interventions to prevent and/or reduce gang-related violence and other harms to health: a systematic review. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the DHSC.