The truth is, you don’t always need a model release form. The question is, when do you have to cover your assets, and when can you shoot freely? Hopefully, we’ll be able to shed some light on some of the confusion. When it comes to video production and the law, it’s essential to cover all of your bases.

For more than a century, photojournalists in the United States have had the pleasure of shooting in almost any situation wherever and whenever they please, because they know that the First Amendment protects their rights to get coverage for their story. The gray area comes about with non-journalists who are in the dark about their implied ‘rights’ and don’t exactly know when or why they might need a model or talent release form.

Imagine all the breathtaking photos taken by noted TIME and LIFE magazine photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White, who traveled the country during the Great Depression, capturing the drawn faces and look of loss and hopelessness of the subjects she photographed so richly. Imagine the horrific images of the realities of war captured by Robert Capa at Omaha Beach and Normandy during World War II. Consider all the video we’ve witnessed coming right off Wall Street and across the country when the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations unfolded. Had those who posted Occupy images all over the web been detained or expected to provide model release forms, we might only have seen a few select shots that were ‘approved’ by the government or Wall Street leaders – images of “scary dangerous long-haired crazy people” – rather that the moving shots of senior citizens using walkers, young families, and average business people. If photojournalists had to get a release form for every shot like those, it certainly would have killed the spontaneity of the moment, and many a camera would have stayed capped due to legal concerns.

An ethical photojournalist works within very well-defined rules. The images must be impartial, honest and tell the story in a way to complement a newsworthy event. They must be objective. The photographers or videographers aren’t allowed to “stage” anything within the event to capture the image they want – they are merely the extension of the eye of the camera. (I know what you’re going to ask next, but let’s not debate the accusations of right-wing or left-wing news slant today; that’s for a different story for another time!)

Photojournalists don’t need releases, they know they are protected under the First Amendment, and if you’re shooting for editorial purposes, neither do you. Newspapers, TV news stations, and online reporters aren’t required to obtain permission to take people’s pictures at newsworthy events. This means if you’re shooting for editorial purposes for a news organization, you shouldn’t have to have permission or releases, either. Usually.

TV news and newspapers, are considered “editorial sources” rather than “commercial” operations. Their chief purpose is to inform and educate. TV stations don’t usually require you to supply a model release, but publications like Videomaker do. Although publications like ours are in the business to “educate and inform,” our photos and videos are illustrative scenes meant to explain an action, event or product – so there’s a gray area with some publications or video outlets. Some establishments that sell footage or apply footage for commercial use might ask for a release before they use your photos or video, or they might simply require you to send them an email granting permission. “Commercial use” means when you are selling the images for anything other than editorial (educational or informational) coverage. If it’s your own work, that’s easy. If it’s someone else’s, or there’s an unnamed person in the shot, you’ll need their permission via a signed release.

The answer to that question is: “It depends.”(You knew I was going to say that, didn’t you?) Even if you’re not starting a production company or trying to sell a shot to a stock media site, if you plan to use images of unknown people for something later on down the road you might need a release, so it’s a good idea to always get one up front.

I don’t want to crush your desire to make the next great documentary, but learn from a page out of my book. After years of shooting for the news, I ventured out to make my own little documentary. I spent all summer getting interviews, shooting a backstory, following builders and congregation members of a 100-year-old church that was going through a rebirth after 50 years of conflict, decay and ruin. I had a terrific story of contention, rot and abuse followed by an awakening like the Phoenix from the ashes; yet I forgot the one thing I needed above all. Thinking the story was only going to serve the tiny congregation for a fund-raiser, I had no idea they’d love it enough to want to ship it to PBS, the History channel or any number of broadcast potentials. But thinking the story would never go beyond the 100-year-old brick walls, I didn’t obtain any authentication of where the historical photos or the licensed music I used originated; I didn’t gather any release forms, and many of the people in the video had moved on. I was stuck. Back-pedaling is the most difficult thing to do in any venture, gathering all the necessary information after the fact is nearly impossible. My doc sits in a shoebox, still unseen.

You’ve probably heard that it’s okay to shoot anywhere, anytime in public, but even if the video you shot was on a public street at a public event there’s a gray area. For example, if you stumble upon a criminal situation or police enforcement – like someone’s arrest, go ahead and shoot away – but do it knowing full well that if the person being arrested ends up getting off due to a false identity, you can get yourself and the news station you sold it to in trouble. So shooter beware.

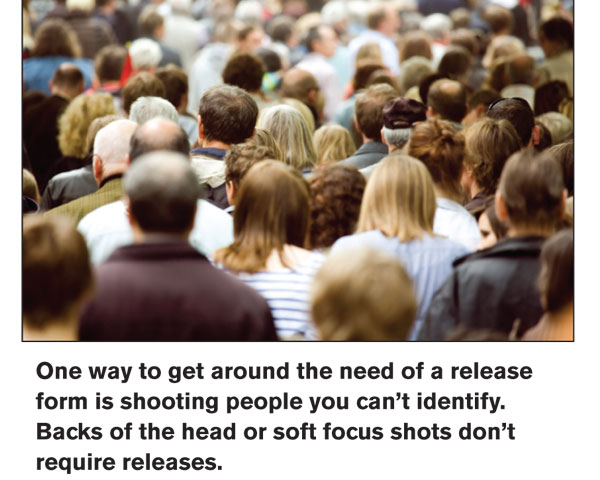

You also need to be sensitive to people’s privacy in public if what you’re covering is a tragic event such as auto accident, house fire, or medical situation. Shooting the medical personnel, firefighters or police activity isn’t considered ‘sensitive,’ but shooting the victim is. Knowing and understanding the differences can be the difference between covering a good story and landing in court – or at least being banned from covering any other story for the station that aired the errant footage. (TIP: News people will shoot half-angles of faces they want to obscure but still use. Let’s face it, angst sells, but a full frontal image of someone’s emotional pain is highly sensitive, so shoot it if you must, but give the editors other choices, too, so that they can make the ultimate decision what to use and what lands on the editing room floor.)

And, yes, sometimes you’ve heard that recording police in the line of action is considered fair game if they and you are on public property, but if you are obstructing traffic, or endangering others, or preventing them from doing their job, they can and will take action against you.

What you shouldn’t do, even if it’s for the news, is use photos or video you’ve gathered after someone has asked you not to use their image. You see, if they’re in a public place, and you’re covering a public event (or a private event you were invited to cover), there’s no reason to get someone mad at you, and subsequently the news organization you are shooting for, just because they asked you not to use a shot and you did anyway. There should be plenty of other things that you can capture with people who would be excited to see themselves on TV. Of course, that ‘one of a kind’ exclusive shot would be hard to pass by – use your judgement there!

Celebrities and famous people in public areas are fair game to a certain degree, and the more famous the public figures, the stronger your right to shoot them. Ordinary citizens in public areas are also fair game, to some extent. But, again, be aware of the sensitivity of the situation.

Consider this example: you need some crowd shots of a bunch of people for two different types of promotional videos that are going to air in PSAs (Public Service Announcements). You go to the busiest intersection downtown during lunch and shoot a wide shot of people walking on the sidewalk towards the camera. Your first PSA is about the wonders of your little town. Your audience will certainly love it. You got that done, but now you want to shoot crowd shots for the next PSA – which is on healthy eating and obesity. You have now just connected those people with a product, service or concept – and that is not okay. The moment you use that shot, any number of people that appear in it might think that you are calling them obese, and how dare you single them out? They are in a public place, you are in a public place, so, technically it’s OK, but doing so can cause grief, which can cause complaints, which can cause a potential lawsuit, which can cause the company you are shooting for to not to use you again.

So you think you have the talent part worked out. What about the location? As long as you are in a public place you think it’s okay, and you might not need to get a location release, but you might need permits to shoot. Many city and state governments have film commissions that run the video red-tape for location shooting permits. This Videomaker forum post directs you to the U.S. Film Commission offices in each state. Each state’s office can tip you to the specific city office. When you need to gather permits for location shooting, plan far enough in advance, and let them know the exact times and dates, along with the amount of gear and the number of crew members. Will you need to shut down streets? Entrances to public buildings? Parks? This requires even more red-tape, so have your needs all planned out as well as a budget for possible processing fees.

Shooting in or at private property requires permission of the owner or authorized agent. Places like your local museum, mall or zoo might seem to be public property, but they aren’t and they have rules for photo and video that are usually printed in the fine print on the back of your entry ticket or in the business office. If you are just shooting a day in the park with family and friends, even if you plan to post it to YouTube, that will be okay, but if you are shooting for commercial purposes, you might not be able to do so without permission. The owners might simply not want you shooting for commercial reasons just because they want to sell their own version of the zoo animals’ antics, for example. They might allow you to shoot a commercial production (or shots for stock footage), but they might not allow lights, tripods, or microphones. It’s up to you to know when and what you can shoot.

If you are shooting for commercial purposes, get a release. If the stock site you’re selling to is commercial, or has several levels of publication, e.g., commercial, for profit, non profit, art; you might not need a release for the non profit page, but you will for the commercial page, so if you want to have ‘full coverage’ it’s a good idea to get permission up front.

Let’s get down to the nitty gritty – you want to know exactly when you really need a release:

Don’t fret – there are lots of places you can freely shoot, even if it’s for commercial purposes, without getting a signed release from the person or agent of the property. For example, unexpected events. If the house across the street explodes into flames, you might rush out to capture the activities surrounding the incident. It’s OK to shoot the fire, the firefighters and the emergency personnel. However, again, be discreet and respectful about shooting other people, especially the grieving family, and don’t allow your camera to linger on bystanders watching. High tension moments like this can get your camera yanked from your hands, and you’ll have a legal battle to work out. You are in your full rights to shoot it, but you risk injury to yourself or your gear in the meantime.

Example: you’re hired by the promoters to shoot a local parade on public streets. There’s no way you’re going to get a release form from every person in the parade and on the street watching. You can have the promoters post signs stating this event is being videotaped, and/or you can ask the promoters to mention this fact over the PA system. The people IN the parade do so knowing they will be photographed, the people on the sidelines do not expect it. You can still show your footage in the news that night without a problem. But if you make a ‘slam’ documentary of your little town later, and use those shots, someone might complain.

Bottom line, we’ve heard a lot of stuff about videographers and photographers being sued for using people’s images, and with all that noise, you’d think the courts would be full, and the jails over-filled with picture-taking shooters instead of gun-toting shooters. Usually when someone wants to sue, they go after the people with the deep pockets, not the lone producer. Usually.

Unless you cover news, most of your shooting will be non-editorial, which means you should have talent release forms at your disposal. The appropriate release should be considered a standard practice of video production, like extra batteries. There are many places where you can find sample forms, including from Videomaker. We sell an enormous “Book of Forms” that has samples of every form you can possible think of, from a model release form template to a talent release form, video production shooting lists, location release forms, video production costs checklists and production tracking lists for when you are starting a production company. Some of these can be downloaded individually on our site, others are bundled together. The entire book can be downloaded or purchased as a printed copy with a CD of the forms.

Most of the language in any talent release form can be edited to be more specific to your needs; however, be aware of the legal lingo, and don’t do too much editing without seeking professional help. See the sidebar for a link to one online release form offered by Videomaker. Also, check out our Videomaker Complete Book of Forms.

For most stock media sites, you are not going to sell one frame of video to a stock footage site if you don’t have releases, and that includes people in your own family. These rules are made by the media sites, not a body of lawmakers. You can’t control how the person who purchases your footage will use it, so many companies require model releases and/or location releases of some kind. If you aren’t required to supply a model release, and your images are accepted and used, you’re not at risk because you have no control over that and you technically license the use of the footage when you sell it to a stock video site.

Consider that you’re shooting a performance, a dance recital, a child’s school program, and the event itself is using copyrighted music. You want to record the event and sell DVD copies to the parents. You know the parents will want to put their kids’ performance on YouTube, and you also know that YouTube might send them a C&D (Cease and Desist) takedown notice. Are you the ultimate responsible party? No, you didn’t put the footage online. However, you knowingly used copyrighted music, so you might want the purchasers of your video or the dance recital organizers to indemnify you for any legal action brought against you for the use of the music.

The one thing to remember above all is that, living in a free country like the United States, you might have the right to shoot almost whenever, whoever or wherever you want, but the person or owners of the location that you are shooting have rights to privacy, and their rights might supersede yours. Be careful. Stay legal. Use your model release forms and location release forms wisely. Be safe out there!

When you don’t have a written release, or when you are interviewing a lot of people in a very short time, you can sometimes get away with a verbal release. You do this by having the person read a short script while on camera. That verbal agreement needs to have the person’s name, the date, the video production company or producers’ name, and clearly defined understanding of what the shoot is for. Here is an example of how one would look*:

(To be read aloud)

I, ________, give ______ the right to use my name, likeness, still or moving image, voice, appearance, and performance in a video program. This grant includes without limitation the right to edit, mix or duplicate and to use or re-use this video program in whole or part. I acknowledge that I have no interest or ownership in the video program or its copyright. I also grant the right to broadcast, exhibit, market, sell, and otherwise distribute this video program, either in whole or in part, and either alone or with other products for any lawful purpose. In consideration of all of the above, I hereby acknowledge receipt of reasonable and fair consideration.

(*From the Videomaker “Videography Tips” webpage.) https://www.videomaker.com/tips-to-get-started

Looking for a good model release form? This link above takes you to a well written and complete online release. Print it and keep it in a folder in your gear bag for those “just in case” moments. Keep copies or re-write the text to suit your needs. This form has passed by the eyes of a content attorney, but your state and regional laws may differ. Remember, any re-writes on forms like this can get you in hot water if you’re not sure of the proper lingo. Take care of you!

This article should be construed as informational, not legal advice. Videomaker does not provide or offer legal advice to its readers. Videomaker, its editors and authors will not be held responsible for any legal issues the reader might encounter based on the subjects found in this feature. We recommend you consult a legal expert for advice on shooting in unfamiliar situations. Videomaker assumes its readers will exercise good common sense. This disclaimer assigns you, our readers, all responsibility for your own decisions.

Jennifer O’Rourke is an Emmy award-winning photographer & editor and Videomaker‘s Managing Editor.

The Videomaker Editors are dedicated to bringing you the information you need to produce and share better video.